Freemasonry is "a system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols". No matter the race, station or creed, all just and upright men, free by birth, of mature age, sound judgment and strict morals may seek membership in our Institution.

The institution gives these men the tools necessary to generate in themselves the inner process of intellectual, moral and spiritual transformation. Aiming for this transformation, the institution guides and provides a methodology which enables each member to generate his own inner light and to reach full and complete mastery of his existence. But the depth and height reached by each member depends on his effort, perseverance and commitment. The goal is clear: to make of himself a new and better man, tolerant of the diversity of others, and desirous of contributing to the progress of all humanity.

Brotherly Love -This tenet, or fundamental principle, is an essential element which binds all Masons to each other, as they have pledged themselves to exercise it and it is one of the greatest duties of a Freemason. On this principle, Masonry unites men of every country, religious belief and opinion in a bond of true friendship. Brotherly Love also manifests itself in the second tenet of relief, which is one form of charity.

Relief - Masonic relief takes for granted that any man may be in temporary need of a helping hand. It can take many forms, such as alleviating misfortune, soothing calamity, helping to restore peace to a troubled mind, and so on. This is one of the natural and inevitable acts of Brotherhood.

Truth - Truth is a vital requirement if Brotherhood is to endure. As Masons, we are committed to being honest and truthful with other people. The Masonic Fraternity teaches a man to be faithful to his responsibilities to God, his Country, his fellow man, his family and himself. The Masonic principle of Truth also teaches a man to pursue knowledge and to search for wisdom and understanding. For only in this way can he grow and become a better person.

47th Problem of Euclid

In the Year 3650 (300 B.C.E.), Anno Mundi, which was 646 years after the building of King Solomon's Temple, Euclid, the celebrated geometrician, was born.

Euclid has been always associated with the history of Freemasonry, and in the reign of Ptolemy Soter, the Order is said to have greatly flourished in Egypt, under his auspices. The well-known forty-seventh (47th) problem of his first book, although not discovered by him, but long credited to Pythagoras, has been adopted as a symbol in Masonic instruction.

The Foundation of Freemasonry?

The 47th problem of Euclid is often mentioned in Masonic publications. In Anderson's "Constitutions" published in 1723, it mentions that "The Greater Pythagoras, provided the Author of the 47th Proposition of Euclid's first Book, which, if duly observed, is the Foundation of all Masonry, sacred, civil, and military...". Being mentioned in one of the first "official" speculative Masonic publications clearly indicates that the 47th problem of Euclid must be important. It is also mentioned in the Third Degree lecture, where we are taught that the "47TH problem of Euclid... taught us to be general lovers of the arts and sciences".

However, it is quite different to be referred to as the "Foundation of all Masonry, sacred, civil and military" that to be referred to as "taught us to be general lovers of the arts and sciences". Has the importance of the symbolism of the 47th problem declined over time for some reason?

In order to understand whether the symbol has declined in importance or not, we first need to look at the 47th problem of Euclid itself.

The Discovery of the 47th problem of Euclid

Euclid wrote a set of thirteen books, which were called "Elements". Each book contained many geometric propositions and explanations, and in total Euclid published 465 problems. The 47th problem was set out in Book 1, which is also known as "The Pythagorean Theorem". Why is it called by both these names? Although Euclid published the proposition, it was Pythagoras who discovered it. We learn from the third degree lecture that:

"This wise philosopher (Pythagoras) enriched his mind abundantly in a general knowledge of things, and more especially in Geometry, or Masonry. On this subject he drew out many problems and theorems, and, among the most distinguished, he erected this, when, in the joy of his heart, he exclaimed Eureka, in the Greek language signifying, "I have found it," and upon the discovery of which he is said to have sacrificed a hecatomb. It teaches Masons to be general lovers of the arts and sciences".

Actually, it was not Pythagoras who directly discovered the rule, as the Egyptians used the same principle for a very long time before Pythagoras, whereby they re-measured their fields after the annual flooding of the Nile washed out their boundary markers. Hence, Pythagoras is probably here referred to as being the one who proved that the process works.

History records that Pythagoras established a society with philosophical, religious and political aims. Shrouded in secrecy, they believed that only by truly understanding the universe could one achieve salvation of the soul, and as Divinity created all things, studying it over a period of several lifetimes, could bring one closer to Divinity itself. As such, it was believed that through study and reason could one start to understand Divinity. Clearly, reason is based on measurable things (such as through numbers and objects), and is easier to understand if expressed in that matter. Hence the society devoted much of its time to the mathematics, including Geometry. This line of thinking was incorporated in Freemasonry, which sets it opposite to the Church, which emphasizes faith over reason. Indeed, Pope Pius IX, in his encyclical, Qui Pluribus, dated 9 November 1846, attacked those who "put human reason above faith, and who believe in human progress." Many people consider this to be a reference to Freemasonry.

This is interesting, because in the Book of Wisdom 11:20 we read:

"Even apart from these, men could fall at a single breath when pursued by justice and scattered by the breath of thy power. But thou hast arranged all things by measure and number and weight."

So the very "measurement of things" the Church objects to is mentioned in Scripture.

However, let us get back to how the 47th problem fits in Freemasonry.

What Does the 47th say?

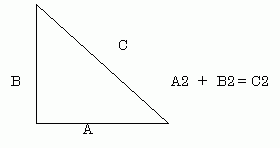

The proposition states that: "In right angled triangles the square on the side subtending the right angle is equal to the squares on the sides containing the right angle."

What? In other words A2 + B2 = C2.

Many readers will feel like they have been returned to Geometry class. A simple illustration will probably refresh our memories.

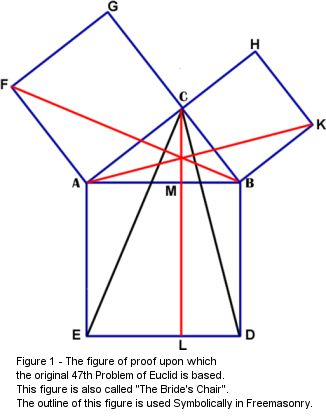

The proposition is especially important in architecture. Builders have since ancient times used the theorem in constructing buildings by a process known as "squaring a room." As the theorem states that 3 squared + 4 squared = 5 squared, a builder starts by marking a spot and drawing a line, say line A. This line is given the value of 3. The builder then marks another point, say point B and draws a line from it at a right angle to line A, and it is given the value of 4. The distance between line A and B is then measured, and if the distance between A and B is 5, then the room is squared. By inverting the process, a "squared" (or rectangle) room can be obtained.

The proposition is especially important in architecture. Builders have since ancient times used the theorem in constructing buildings by a process known as "squaring a room." As the theorem states that 3 squared + 4 squared = 5 squared, a builder starts by marking a spot and drawing a line, say line A. This line is given the value of 3. The builder then marks another point, say point B and draws a line from it at a right angle to line A, and it is given the value of 4. The distance between line A and B is then measured, and if the distance between A and B is 5, then the room is squared. By inverting the process, a "squared" (or rectangle) room can be obtained.

Engineers who tunnel from both sides through a mountain use the 47th problem to get the two shafts to meet in the center. The surveyor who wants to know how high a mountain may be ascertains the answer through the 47th problem. The astronomer who calculates the distance of the sun, the moon, the planets, and who fixes "the duration of times and seasons, years, and cycles," depends upon the 47th problem for his results. The navigator traveling the trackless seas uses the 47th problem in determining his latitude, his longitude, and his true time. Eclipses are predicted, tides are specified as to height and time of occurrence, land is surveyed, roads run, shafts dug, bridges built, with the 47th problem to show the way.

In some lodges, using this principle, a candidate symbolically "squares the Lodge" by being escorted around the Lodge three times during the Entered Apprentice ritual, four times for a Fellowcraft ritual, and five times for a Master Mason ritual, which completed his journey.

The 47th problem forms the basis of all ancient measurement units:

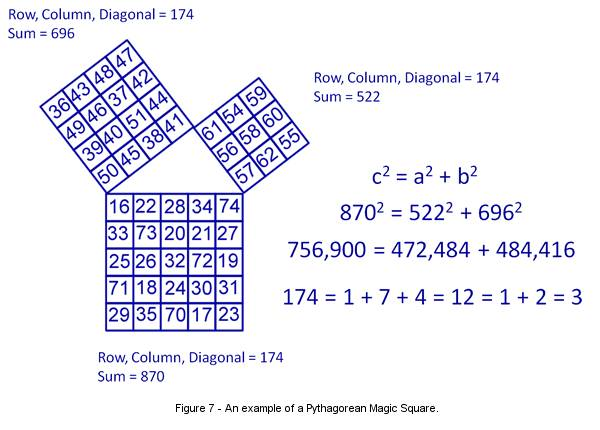

The 47th problem of Euclid formed the basis of a common set of measurements used by the Egyptians, especially in the building of the Great Pyramids. It gets a little technical, but a simple illustration will help us understand it better.

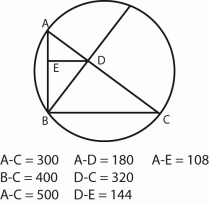

Please see the illustration above, which is not accurate due to a drawing, but will serve to illustrate the point. If we take a circle and draw in it a triangle (triangle A-B-C) which perpendicular is 300, base is 400, and by the 47th problem, the hypotenuse becomes 500 (any combination such as 3,4,5 will also work ? higher numbers are used for ease of explanation). Then if we draw a line from the angle of the perpendicular and the base through the hypotenuse to the circle, this line will be equal to 480.

The resulting two parts of the hypotenuse (A-D and D-C) will be equal to 180 and 320 respectively. Then if we draw another line from the point D (the intersector of the hypotenuse) to the perpendicular of the shortest side of the triangle (A-B), then line A-E will equal 108 and line D-E will equal 144.

Now we have all the measurements of the ancient world, that is 500, 480, 400, 320, 180, 144 and 108. Why is this important? If we take each unit to be a cubit (an ancient form of measurement), then 500 is the base of the Great Pyramid of Memphis. 400 cubits is the length of an Egyptian stadium (stadium is plural for stadia, and ancient measurement unit, based on a particular number of steps, also called a Khet by the Egyptians). 480 cubits is the length of the Ptolemy stadium, 320 cubits is the length of the Hebrew and Babylonian stadium. Furthermore, 180, which represents the smaller part of the hypotenuse, doubled gives 360 cubits, the Cleomedes stadium. By doubling 144 cubits gives 288 cubits, the Archimedes stadium. Finally by doubling 108 cubits we obtain 216 cubits, or the lesser Egyptian stadium.

In other words, this simple exercise formed the basis of all the lengths used by the Egyptians, and hence also once again indicates that its principle was well understood by the Egyptians, and hence taught by them to Pythagoras.

Conclusion

Clearly, the 47th problem helps us look at the universe, and all that is in it, through a system that we can understand clearly, for it is measurable. The Master's jewel is the square, the base needed for the 47th problem (in many jurisdictions the square has the dimensions of 3:4 ? the Pythagorean dimensions). As the Master serves his position, he becomes more complete, and therefore the 47th problem of Euclid is dedicated on his jewel when he leaves office.

References:

Circumambulation and Euclid's 47th proposition, by Reid McInvale

Encyclopedia of Freemasonry, by Albert Mackey

Freemasonry, A journey through ritual and symbol, by W. Kirk

Master Mason, by Carl Claudy

The Philosophy of Freemasonry - We have searched the internet for this topic and the search has returned (November 2006) over 300,000 results. We have examined several of them and found, with few exceptions, that none deals strictly with the philosophy of Masonry, but gives it in combination with the history and practices of Freemasonry, its symbolism, and often colored by particular biases.

In order to relieve the members of our lodge and our visitors, in their search into the philosophy of Masonry, from the burden of sorting out this material, we offer the compilation of works researched by our Bro. Vincent Lombardo. We have provided at the end of the paper some relevant links, where a more in-depth study can be pursued.

An Introduction to the Philosophy of Masonry

* Excerpts from Johann Gottlieb Fichte's lectures, titled

"LETTERS TO CONSTANT"

Translated by Bro. Roscoe Pound

Before we go into the subject of our lecture, I must disclose that the bulk of my information is derived from a little-known book I found while searching for the works of Bro. Johann Gottlieb Fichte, a German philosopher of the 18th century.

In 1953 The Supreme Council 33° Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, Northern Masonic Jurisdiction, published a collection of Masonic Writing and Addresses of Bro. Roscoe Pound, which includes his translation of Fichte's Masonic Lectures titled "Letters to Constant." The Supreme Council has given me permission to utilize the material contained in that publication. Most of the information that follows is copied from that book.

Let's begin with a question, a question many non-Masons (and Masons alike) ask:

What is Freemasonry? What made this FRATERNITY to exist, and continue to exist even today, almost 300 years after coming out of the closet?

In most parts of the world the social, political, religious and moral environments have continually changed from that of the 18th century England. Our view of the world and of life in general has changed, our needs have changed, but men have continued to join the fraternity. Why?

Here is how Fichte describes Masonry to Constant:

"You know that in the first decades of the eighteenth century, in London, a society came into public notice, apparently from nowhere, about which no one knew what it was, and what it sought. It spread, notwithstanding, with inconceivable rapidity and traveled over France and Germany, into all states of Christian Europe, and even to America. Men of all ranks, regents, princes, nobles, the learned, artists, men of business, entered it; Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists were initiated and called one another "Brother."

"It is true, wise and virtuous men busy themselves earnestly with the order. It is a fact. But with what do they busy themselves? With the order as it is, or how and what it, and indeed through it, may come to be? ... As certainly as wise and virtuous men at any time busy themselves earnestly with the order of Freemasons, so certainly it can have a reasonable, good, and lofty purpose. This purpose, possible or actual, we shall now find as we go forward upon this path. That is, we can know what the wise and virtuous man can will, what he necessarily must will, so certainly wisdom and virtue are but one and are determined by eternal laws of reason. Therefore we must now investigate what the wise and good man may aim at in such a society. Then we have found with demonstrated certainty the one possible purpose of the order of Freemasons."

"Masonry raises all men above their vocation. In that it trains men, it directly trains the most serviceable members of the greater society–the amiable and popular, the learned and wise, not only the skilful but also the men of affairs possessed of judgment, the humane warriors, the good heads of households, and good bringers-up of children. Whatever human relation one may think of, Masonry has the most advantageous influence upon it."

What I will try to do this evening is to give you a handful of seeds for you to plant, grow, care for, and harvest at your own pace and desire. But first a few words ...

About Roscoe Pound (*1):

His curriculum vite is several pages long and I am not going to read it. Suffice to say that Bro. Pound is considered one of the most accomplished and influential American jurist of our times, and - to have an idea of the amount of his writings - just consider that the index of his works is over 190 pages long.

Born in Lincoln, Nebraska on October 27, 1870, Pound went through a stellar career in the field of law as lawyer, law professor at Harvard and other American universities, and was for a time Supreme Court Judge. He was conferred honorary degrees of Master of Laws, Doctor of Human Letters, and Doctor of Laws by two dozen American universities, and the Berlin University in 1934 conferred on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Canon and Civil Law.

Bro. Pound was initiated in Lancaster Lodge, No. 54, Lincoln, Nebraska, June 14, 1901 and became its W. Master. He was a member of several lodges and other bodies throughout the U.S., Grand lodge officers and received the 33°, September 16, 1913. In 1952 was awarded the Gourgas Medal by the Supreme Council 33°, Northern Masonic Jurisdiction "In recognition of notably distinguished service in the cause of Freemasonry, humanity and country."

Pound tells us that in all human interactions usually there are several points of view - and disagreements. The works of philosophers are not exception - nor are Masonic scholars in perfect harmony with respect to the scope and purposes of Masonry.

There is however, continues Bro. Pound, a well-defined common characteristic in Masonic learning which has to do with three fundamental questions:

What is the nature and purpose of Masonry?

What is (and what should be) the relation of Masonry to other human institutions?

What are (or what should be) the fundamental principles by which Masonry attains the end it seeks?

There are four well-known Masonic scholars who have postulated answers to these questions, and in so doing have given us systems of Masonic philosophy. They are:

William Preston, Karl Christian Friedrich Krause, George Oliver, and Albert Pike. And then there is Johann Gottlieb Fichte - a scholar and philosopher almost unknown in this continent - whose work parallels and surpasses (in my view) the works of the previous four.

I will now give you a brief outline of the philosophy of the first four, and then speak at length of Fichte's work. Preston's focus is on Knowledge; Krause's is on Morals; Oliver focuses on Tradition; Pike focuses on Symbolism. Fichte's focus is on Social Harmony.

Pound tells us that the philosophies of each Masonic Writers grew out of the philosophical situation at the time when each of them thought and wrote - and also out of their own personal experience.

- Preston wrote in the so-called "Age of Reason," and Knowledge was to him the most important thing.

- Krause wrote when moral philosophy was a chief concern in Germany and he was, by profession, the leader in the philosophy of law in his time.

- Oliver wrote under the influence of Romanticism in England, at a time when German Idealism was coming into English thought.

- Pike wrote under the influence of the reaction from the materialism of the last half of the nineteenth century and under the influence of the nineteenth-century metaphysical method of unifying all things by reference to some basic absolute principle.

To Preston, Masonry is a traditional system of knowledge and its end is to impart knowledge. Therefore he thinks of Education as the essence of Masonry.

To Krause it is organized morals and its end is to put organized mankind behind the universal moral ideas of humanity. Hence he thinks of the relation of Masonry to law and government.

To Oliver Masonry is a mode of approach to God and its end is to bring us to the Absolute by means of a pure tradition. To him, Masonry means Religion.

To Pike Masonry is a mode of studying first principles, and its end is to reveal and to give us possession of the universal principle, by which we may master the universe.

Let's briefly look at the men [I have condensed Bro. Pound's narrative]:

William Preston (*2)

Was born at Edinburgh on August 7, 1742. His father was a kind of a clerk in the legal profession and seems to have been a man of some education and ability. William was sent to the high school at Edinburgh at an early age. His father died while William was a mere boy and he was taken out of school, apparently before he was twelve years old.

His father had left him to the care of Thomas Ruddiman, a well-known linguist, and he became Ruddiman's clerk. Later Ruddiman apprenticed William to his brother who was a printer, so that Preston learned the printer's trade as a boy of fourteen or fifteen and worked there as a journeyman until 1762.

In that year, with the consent of the master to whom he had been apprenticed, he went to London carrying a letter of recommendation to the king's printer, where he found employment at once. In short time he was made proofreader and corrector for the press and worked as such during the greater part of his career.

As soon as he reached the age of 21, Preston was made a Mason in a lodge of Scotchmen in London. At the age of twenty-five he became Master of the lodge, and as such conceived to be his duty to make an in-depth study of the Masonic institution.

He corresponded with all well-informed Masons abroad and taking advantage of every opportunity to interview Masons at home. The results of this communication with all the prominent Masons of his time are to be seen in his lectures.

In those days, the candidates for initiation were read "The CHARGES of a FREE-MASON" and the practice was of orally expounding their contents and commenting upon the important points. Preston determined to rewrite the lectures of Craft Masonry, and to turn them into a system of fixed lectures and give them a definite place in the ritual.

When Preston began the composition of his lectures, he organized a sort of club, composed of his friends, for the purpose of listening to him and criticizing him. This club met twice a week.

In 1772, after seven years, he interested the grand officers in his work and delivered an oration before a meeting of eminent Masons including the principal grand officers.

After delivery of the oration, they approved the lectures. Preston and his friends then went from lodge to lodge delivering his lectures and came back to their weekly meetings with criticisms and suggestions.

By 1774 his system was complete. He then instituted a regular school of instruction, which obtained the sanction of the Grand Lodge and thus diffused his lectures throughout England. This made him the most prominent Mason of the time, so that he was elected to the famous Lodge of Antiquity, one of the four old lodges of 1717. He was soon elected Master of this Lodge and continued as such for many years, giving the Lodge a pre-eminent place in English Masonry.

In addition to his lectures, Preston's book, Illustrations of Masonry, has had great influence. It went through some twenty editions in England, four or five in America, and two in Germany.

Preston's Philosophy of Masonry and his lectures are the work of a printer, the son of an educated father, but taken from school before he was twelve. Therefore he was chiefly self-educated by picking up everything he could from the manuscripts passing through his hands at the shop and by tireless labor at night in reading them, and by interacting with the authors of his time. His work reflects the cardinal notions of the time - Intellectualism.

Let's go back to the three fundamental questions of Masonic learning:

(1) What is the nature and purpose of Masonry?

The answer we find in Preston is: to spread knowledge among men - as knowledge makes men better, wiser, and consequently happier. To Preston, Masonry exists to promote knowledge.

(2) What is the relation of Masonry to other human institutions?

To Preston, the state makes men better and happier by preserving order. The church does the same by cultivating the moral person and by holding in the background supernatural sanctions. Masonry supplements church and state by teaching and by diffusing knowledge among men.

(3) What are (or what should be) the fundamental principles by which Masonry is governed in attaining the end it seeks? Preston answers that both by symbols and by lectures the Mason is (first) admonished to study and to acquire learning and (second) is actually taught a complete system of organized knowledge.

Karl Christian Friedrich Krause (*3)

Was born at Eisenberg, not far from Leipzig, in 1781. He was educated at Jena where he studied philosophy under professors Friedrich W. Schelling, Georg Hegel and Johann Gottlieb Fichte, and where he taught for some time as privatdozent. In 1805, he moved to Dresden to teach philosophy of law. In the spring of that year he was initiated into Masonry in the Loge Archimedes zu den drei Reißbretern in Altenburg and later, on the 31st of October 1805, on the recommendation of Lodge Archimedes, affiliated with the Zu den drei Schwerdtern und den wahren Freunden in Dresden. At once he entered upon a critical and philosophical study of the institution, reading every Masonic work then available. As a result of his studies, he delivered twelve lectures before his lodge in Dresden, which were published in 1809, under the title:

Höhere Vergeistung der echt überlieferten Grundsymbole der Freimaurerei

(Higher Spiritualization of the True Traditional Fundamental Symbols of Masonry)

A year later he published the first volume of his great work:

Die drei ältesten Kunsturkunden der Freimaurerbruderschaft

(The Three Oldest Craft Records of the Masonic Fraternity)

This book, one of the most learned ever issued from the Masonic press, immediately caused him great grief. The limits of permissible public discussion of Masonic symbols were then uncertain, and the liberty of the individual was not wholly conceded by the German Masons of that day. The very rumor of Krause's book produced great agitation. Extraordinary efforts were made to prevent its publication, and, when these failed, the mistaken zeal of his brethren was exerted toward expelling him from the Order. Not only was he excommunicated by his lodge, but the persecution to which his Masonic publications gave rise followed him all his life, and prevented him from receiving public recognition of the position he occupied among the thinkers of his day.

In his philosophy of Masonry and his philosophy of law Krause makes the distinction between the natural order, the social order, and the moral order.

To Krause the natural order is typified by the ceaseless and relentless strife in which all individuals, races, and species are inevitably involved. He uses as example the struggle of every weeds at war with one another for room to grow, but must contend for their existence against the ravages of insects, the voracity of grazing animals, and the implements of men. Thus, the staple of life, under pure natural conditions, is conflict.

If we turn to the artificial conditions of a garden, the contrast is extreme. Even exotic species, planted carefully, so as not to interfere with each other, carefully tended, turn their whole energies to more perfect development, and produce forms and varieties of which their rude, uncultivated originals scarcely convey a hint.

To Krause, society and civilization are, like a garden, an artificial order. As in the garden, so in society, the characteristic feature is elimination of the struggle for existence.

To him, religion governs men by supernatural sanctions; morality governs them by the sanction of private and public opinion; the state governs them by the sanctions and force of the organized law.

To Krause, the Masonic order is the most suited institution in cultivating morality worldwide - respecting every honest creed, but requiring adherence to none.

Thus, he conceives that Masonry is working hand-in-hand with church and state, in organizing the conditions of social progress; since each and all, held up by the three pillars of the social order - Religion, Law, and Morals; Wisdom, Strength, and Beauty - are making for human perfection.

Let's go back to the three fundamental questions of Masonic learning:

(1) What is the nature and purpose of Masonry as an institution? The answer we find in Krause is: The perfection of humanity.

(2) What is (and what should be) the relation of Masonry to other human institutions? Krause says: each of these organizations should work in harmony and even in co-operation with the others toward the great end of all of them.

(3) What are (or what should be) the fundamental principles by which Masonry is governed in attaining the end it seeks? Krause answers: Masonry has to deal with the internal conditions of life governed by reason. Hence its fundamental principles are measurement and restraint - measurement by reason and restraint by reason - and it teaches these as a means of achieving perfection.

George Oliver (*4)

According to Pound, Krause's philosophy is concerned chiefly with the relation of Masonry to the philosophy of law and government. Oliver's philosophy of Masonry deals with Masonry in its relation to the philosophy of religion. In order to understand this we need to note that Krause was by profession a philosopher and that the main work of his life was done in the philosophy of law and of government, while Oliver was a clergyman who wrote extensively about ancient texts.

George Oliver was born the county of Nottingham, November 5, 1782. His father was a clergyman of the established church; hence he had the advantage of a bringing up under conditions of culture and refinement. Oliver's father was a well-informed Mason and a ritualist of the literal school, that is, of the type who regards literal rendition of the ritual as the ESSENCE of Masonry. Accordingly, Oliver was trained on this practice and as a result of his thorough knowledge of the work and his tireless activity his rise in the Craft was rapid.

Oliver was made a Mason at the age of nineteen. He was initiated by his father in St. Peters Lodge at Peterborough in 1801.

In 1809 Oliver established a lodge at Grimsby where he was the master of the grammar school and chiefly by his efforts the lodge became strong and prosperous. He was Master of that lodge fourteen years. Thence successively he became Provincial Grand Steward; Grand Chaplain; and Deputy Grand Master.

The list of Oliver's Masonic writings is very long. He is the most prolific of Masonic authors and on the whole has had the widest influence. He began by publishing a number of Masonic sermons and then he turned his attention to the history and to the philosophy of the Craft.

Now for the time:

The dominant philosophy everywhere when Oliver wrote was what is known as Romanticism. In England, which at this period was still primarily taken up with religious rather than with philosophical or scientific questions, romanticism was especially strong. Oliver's philosophy of Masonry is characterized by three important points:

1. His theory of the relation of Masonry to religion;

2. His theory of Masonry as a tradition coming down to us from a pure state prior to the flood;

3. His theory of the essentially Christian nature of our institution.

Briefly stated Oliver's theory is this:

He held that Masonry was to be found as a body of tradition in the earliest periods of history as recorded in Scripture. This tradition, according to his enthusiastic speculations, was taught by Seth to his descendants and was practiced by them as a pure or primitive Masonry before the flood. Thus it passed over to Noah and his descendants and at the dispersion of mankind was divided into pure Masonry and spurious Masonry. The pure Masonry passed through the patriarchs to Solomon and thence to the present institution.

On the other hand, the pure tradition was corrupted among the pagans and took the form of the mysteries and initiatory rites of antiquity. Accordingly, he held, we have in Masonry a traditional science of morality veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols.

Oliver's answers to the three fundamental questions of Masonic philosophy:

(1) What is the purpose of Masonry? To Oliver, religion and science are the means through which we know God and his works.

(2) How does Masonry seek to achieve its end? Oliver would answer: by preserving, handing down and interpreting a tradition of immemorial antiquity.

(3) What are the fundamental principles by which Masonry is governed in achieving its task? Oliver would say: the fundamental principles of Masonry are essentially the principles of religion and the basis of the moral world. But in Masonry they appear in a traditional form. Thus, for example, toleration in Masonry is a form of what in religion we call charity; universality in Masonry is a traditional form of what in religion we call love of one's neighbor.

Albert Pike (*5)

Was born in Boston, December 29, 1809. His parents were poor. He was educated in the public schools in Boston and it is interesting to know as a means of comparing those days with these that, although he passed the examinations for admission to Harvard College, he was unable to enter because in those days the requirement was that two years' tuition be paid in advance or secured by bond. He became a schoolteacher and taught in country schools from 1825 to 1831. In 1831 he went west and joined a trading party from St. Louis to Santa Fe. He was involved in a duel but no one got hurt. On his return he settled at Van Buren in Arkansas where he opened a school. In 1853 he moved to New Orleans were he practiced law up to 1857. Here he made a diligent thorough study of Roman law, the basis of the French law, which existed then, as it does now, in Louisiana. In 1857 he returned to Arkansas and afterward sat upon the supreme bench of that state.

Let's go back to the three fundamental questions of Masonic learning:

(1) What is the purpose of Masonry? To Pike, the immediate end is the pursuit of light. Hence the ultimate end is to lead us to the Absolute.

(2) What is the relation of Masonry to other human institutions and particularly to the state and to religion? To Pike, Masonry teaches us that there is but one Absolute and that everything short of that Absolute is relative; just a manifestation, so that creeds and dogmas, political or religious, are only interpretations.

(3) How does Masonry seek to reach these ends? He would say by a system of allegories and of symbols handed down from antiquity which we are to study and upon which we are to reflect until they reveal the light to each of us individually. Masonry in Pike's view is nothing less than the whole history of human search for reality. And through it - through the mastery of it, according to Pike, we shall master the universe.

Now to Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte (*6),

One of the great idealist philosophers of the end of the eighteenth and for part of the nineteenth century, was born at Rammenau in upper Lusatia (Ober Lausitz) May 19, 1762. Lusatia, a district between the Elbe and the Oder, was then a part of Saxony. In the settlement after the Napoleonic wars in 1815 it became part of Prussia.

Fichte had the best of education at the famous school at Pforta and at the Universities of Jena and Leipzig. After leaving the university he acted for a time as a private tutor and teacher in different families in Saxony, Zurich, and Leipzig and, for a time, in Warsaw. After many ups and downs of fortune, he visited Kant at Konigsberg. To attract Kant's attention, he wrote an essay entitled "Essay toward a Critique of all Revelation" in which he applied the principles of Kant's critical philosophy to investigation of the conditions under which religious belief was possible. Kant approved the essay and helped find a publisher. It was published anonymously in 1792 and was generally attributed to Kant.

Kant corrected the mistake, commended the essay, and the reputation of the author was established. In 1793, he became professor of philosophy at Jena and at once proved an outstanding teacher. During the next five years he published a number of books, which make up his system of philosophy.

In 1798, as editor of the Philosophical Journal, he received from a friend a paper on the "Development of the Idea of Religion" which he prefaced with a paper on "The Grounds of Our Belief in a Divine Government of the Universe" and printed in the Journal.

Theological ideas were rigid at that time, and a bitter controversy arose as a result of which Saxony and all the German states except Prussia suppressed the Journal. Fichte in 1799 resigned his professorship and went to Berlin. He lived in Berlin until 1806, except that he lectured at Erlangen in the summer of 1805. While in Berlin he wrote some of his most important books. But in 1806, the French occupation drove him out, and he lectured for a time at Konigsberg and at Copenhagen.

He returned to Berlin in 1807 and on the founding of the University of Berlin (for which he had drawn up the plan) he was its first rector (1810-1812). In one of the epidemics of typhus which accompanied the Napoleonic Wars, he was taken with what was called hospital fever, and died on January 27, 1814 - at the age of fifty-two.

Fichte was made a Mason in Zurich in 1793, the year in which he went to Jena as professor of philosophy [one of his pupils was Krause]. But in Jena there had been no lodge since 1764, so he affiliated with the Gunther Lodge of the Standing Lion at Rudolfstadt (in Thuringia, 18 miles from Jena) of which the reigning Prince was patron. When he went to Berlin in 1799 he met Fessler, the Deputy Grand Master of the Grand Lodge Royal York of Friendship, in which he soon became active.

In 1802, Fichte, at Fessler's instance, wrote two lectures on the philosophy of Masonry, the manuscript of which he gave to Johann Karl Christian Fischer, the Master of the Inner Orient, who published them as "Letters to Constant" in 1802-1803. The first lecture develops the idea of a separate society for general human development and so comes to the setting up of a theory of social harmony. The second lecture develops the form of Masonic instruction through myth and ritual for the purpose of making cultivated men for that society.

Why two lectures on the philosophy of Masonry written originally for a lodge were changed to sixteen "Letters to Constant" - addressed to "an imaginary non-Mason," named Constant?

In those times, the limits of permissible public discussion of Masonic matters were not clear, [remember what happened to Krause!] and the liberty of the individual Mason to interpret for himself was not generally conceded. Fischer in 1803 thought it wise that the two Masonic lectures be published under the form of letters addressed to a non-Mason by one who professed only to know what, on philosophical principles, Masonry ought to be. It is not known for certain why the recipient of the letters was called Constant.

Let's go back to the three fundamental questions of Masonic learning - one at the time:

(1) What is the nature and purpose of Masonry as an institution?

Masonic literature of the time did not discuss the question. Mostly derived from or elaborated on the basis of the Old Charges, it had to do with a largely mythical story of the transmission of civilization from the biblical patriarchs and by the Hebrews, the Phoenicians, the Greeks, and the Romans to the Middle Ages.

Preston's Illustrations of Masonry, from French discussions of the symbols, and from some pious discourses which had begun to appear, could not satisfy a philosopher - this is amply clear from the very first paragraph of Fichte's letters:

"You cannot reasonably ask that I concede to you any other acquaintance with the order than that it exists. What you would know from your books as to the nature of its existence I cannot recognize since all this literary trash has begotten no knowledge in you and has only entangled you in contradiction and doubt. What writers are you to trust if you have no measure by which to test them and no means whereby to reconcile them? And as to what you believe or, as you say, you may find more or less likely by a historical critique, I appeal to your own feeling as I assert that your actual knowledge of the matter, taken strictly, extends to no more than the existence of the order ... But this is complete enough for me and I invite you to add to this sure knowledge conclusions quite as sure. Then shall we find what the order of Free Masons is in and of itself? No, not that. But what it can be in and of itself, or, if you like, what it ought to be."

Pound tells us that philosophical systems grow out of attempts to solve concrete problems of a time and place. The philosopher finds a satisfying solution and puts it in abstract, universal terms. Then he or his disciples make it or seek to make it a universal solvent, equal to all problems everywhere and in all times.

Accordingly, Fichte starts with the urgent concrete problem of Masonry in his time. It appeared to be hopelessly divided into systems and sects and rites. In England, the schism of the self-styled Ancients had produced two Grand Lodges, each claiming to be the true successor of the Masonry which had come down from antiquity through the Middle Ages. On the Continent, and Germany in particular, things were much worse with the pulling and hauling of rival sovereign bodies, the claims of self-constituted leaders to property in the high degrees and the downright peddling of them, had produced an even worse condition. Therefore it was necessary to go back to first principles and determine (in reason) what Masonry could be and what it ought to be.

What in reason an immemorial universal brotherhood could do and should be doing?

In answering this question Fichte had before him the social, political, and economic condition of Europe, and in particular of Germany in his time - and his philosophical dream of an ideal of human perfection or, if you will, civilization. What impressed him as a child growing up through adversity was the gulf between the cultivated, professional man, the less cultivated practical man of business, and the uncultivated man in the humbler walks of life, each, however wise in his calling and however virtuous, suspicious of the others, unappreciative of the others' purposes, and very likely intolerant of the others' plans and proposals. Thus there was in society the same unhappy cleavage, which he saw in the Masonry of the time.

He saw the same phenomenon also in the political order. The medieval academic ideal of political unity of Christendom had broken down in the sixteenth century and had been superseded by nationalism. Since that time Christendom had been torn by successive wars between nations seeking political hegemony, and, when Fichte wrote, the wars of the French Revolution and empire were still waging.

Society in Western Europe seemed hopelessly divided into states unable to work together except in fluctuating alliances and then not toward any common goal of humanity or of civilization but only toward political self-aggrandizement.

In Germany, not yet unified politically, but divided into more than two dozen states, in more or less constant strife with each other, the political condition of Europe was reflected in aggravated form.

A like phenomenon was appearing in the economic order. The organized society of the Middle Ages had broken down. The French Revolution had put an end to feudal society in France and it was spreading to central Europe. Economic freedom of the middle class was increasingly given this class political control.

The proletariat was emerging to class-consciousness and was making continually increasing demands. Thus there was emerging a class-organized society which has been a conspicuous feature of the economic order following industrialization, which has gone on everywhere since the end of the eighteenth century. States, classes, professions, and walks of life alike were suspicious of each other, intolerant of each other.

Society in Europe, which was culturally a unit and had inherited a universal tradition from the Middle Ages, was in chaos and in a condition of internal strife and conflict which stood in the way of the progress of civilization. Even the unity of the church, which had held men together to some extent during the Middle Ages, had disappeared at the Reformation, and sects and denominations were suspicious, and intolerant among themselves.

Thus Fichte looked at the problem presented by the condition of Masonry in his time as part of a problem of all humanity and sought a solution that would enable Masonry to meet or help meet a great need of mankind. Indeed, according to Pound, Fichte's Masonic philosophy is in a sense a part of a larger social and political philosophy in which it is now considered that he laid the foundation of much of the social philosophical thinking of today.

In those days, each man was trained for some profession or vocation and, as he perfected himself for the purposes of that profession or vocation, he narrowed his outlook upon the world and came to look upon his fellow men as it were through the visual filter of his profession. Looking at other callings through these lenses, he became suspicious, prejudiced, and intolerant and so largely incapable of assisting in the maintaining and furthering of civilization. In Fichte's words:

"Now every individual develops himself specially for the station in life which he has chosen. From youth on, either through choice or chance he has been destined exclusively for one vocation. That education is held best which prepares the boy most suitably for his future calling. Everything is left on one side which does not stand in the nearest relation to this calling or, as we say, cannot be used. The young man destined to be a scholar spends his whole time learning languages and sciences, indeed with choice of those which further his future breadwinning and with careful putting aside of those which promote the general development of scholarship. All other stations in life and activities are foreign to him, as they are foreign to each other. The physician directs his whole attention only to medicine, the jurist to the law of his country, the merchant to the particular branch of trade in which he is engaged, the manufacturer only to the making of his product. In his specialty he knows with much clearness and thoroughness what he needs to know. It is specially clear to him. He looks on it as his acquired property. He lives in it as in a home. And all this is good. In this way every one does his duty. The reverse would not promote all the advantages of society but would be ruinous to the individual as well as to the whole.

But out of this there arises necessarily with all a certain incompleteness and one-sidedness which commonly, though not necessarily, passes into pedantry ... Thus one-sidedness prevails everywhere, useful here and injurious there. Thus each individual is not simply a learned man; he is a theologian or a jurist or a physician. He is not simply religious; he is a Catholic or a Lutheran or a Jew or a Mohammedan. He is not simply a man; he is a politician or a merchant or a soldier. And so everywhere the highest possible development of vocations hinders the highest possible development of humanity, which is the highest purpose of human existence. Indeed, it must be hindered since everyone has the indispensable duty to make himself as perfect as possible for his own special calling, and this is almost impossible without one-sidedness"

There was need therefore, according to Fichte, of an organization separate from the greater society, in which men were to be given or led to an all-round development, instead of the one-sided vocational development, which they acquired in a society based on division of labor.

In Fichte's words:

"We have recognized it as an evil that education in the greater society is always bound up with a certain one-sidedness and superficiality which stands in the way of the highest possible, i.e. purely human, development and hinders the individual man as well as mankind as a whole from a happy progress to the goal ... We now have a purpose: - To do away with the disadvantages in the mode of education in the greater society and to merge the one-sided education for the special vocation in the all-sided training of men as men.

This is a great purpose since it has for its object what is of most interest to man. It is reasonable in that it expresses one of our highest duties. It is possible since everything is possible that we ought to do. It is almost impossible to attain in the great society, at least exceedingly hard, since walk of life, mode of living, and relations entangle man with fine but fast ties and pull him around in a circle, often without his being aware of it, where he should go forward. Hence the purpose is only to be attained by getting apart. But not by an ever during departure, since a new one-sidedness would arise from that; since thereby the advantages for society of what has been won for pure human development would be lost; and since thereby we disregard that we are to merge both forms of training and thereby to elevate the needful training for vocations. Nor are we to attain the purpose by turning back to isolation, since this would strengthen our one-sidedness more than it would remove it and overlay our heart with an egoistic crust. Therefore we shall attain the purpose only through a society distinct from the greater society which does no injury to any of our relations in that greater society, which has prepared us to see and take to heart in time the purpose of humanity, to make it intentionally ours, and which works through a thousand means to wean us from our vocational and social crudities and raise our development to a purely human one.

This or none is the purpose of the society of Freemasons; so certainly the wise and virtuous man may occupy himself with it. The Mason who was born a man, and has been shaped through the training for his vocation, through the state, and through his other social relations, may be developed again on this platform wholly and thoroughly to a man. This only can be the purpose of a separate society, and it answers the question put to us: What is the order of Freemasons in and of itself, or, if you prefer, what can it be?"

To Fichte then, the purpose of Masonry must be an all-round development of men; not merely as fellows in a calling, citizens of a state, members of a class or members of a denomination, but as men conscious of the duty to rise above suspicion, prejudice, and intolerance, and appreciate and work sympathetically with their fellowmen in every walk of life, of every political allegiance, and of every creed.

Says Fichte:

"This, as I think, is the picture of the ripe, developed man: His mind is free from prejudices of every sort. He is master in the realm of ideas and looks out over the region of human truth as widely as possible. But truth is for him only one - a single indivisible whole, and he puts no side of it before another. To him, development of the spirit is only a part of the whole development, and it does not come into his mind to have entirely completed it, even so little as it comes into his mind to wish to be deprived of it. He sees very well and does not hesitate to acknowledge how much others in this respect behind him are backward, but he is not overzealous about this since he knows also how much here depends upon luck. He obtrudes his light, and much less the full shine of his light, upon no one, while yet he is ever ready to give to anyone who asks it so much as he can carry, and to give it to him in such dress as is most agreeable to him, and does not mind if no one asks enlightenment of him. He is righteous throughout, scrupulous, strict against himself within him self, without externally making the least fuss about his virtue and obtruding it upon others through assertion of his integrity through great conspicuous sacrifices, or affectation of high seriousness. His virtue is as natural and I might say modest as his wisdom; the ruling feeling as to the weaknesses of his fellow men is good-hearted pity; in no wise angry indignation. He lives in faith in a better world already here below, and this faith in his eyes gives value, meaning and beauty to his life in this world; but he does not press this faith upon others. Instead, he carries it within himself as a private treasure. This is the picture of the perfected man; this is the ideal of the Mason. He will not ask nor boast a higher perfection than mankind everywhere can attain. His perfection can be no other than a human and the human perfection. Each man must be busied continually in approximation to this goal. If the order has any efficacy, every member must visibly and consciously occupy himself with this approximation. He must keep this picture before his mind as an ideal set up and laid next to his heart. It must be, as it were, the nature in which he lives and breathes.

It is very likely that not all, yes perhaps no one, of those who call themselves Masons will reach this perfection.

But who has ever measured the goodness of an ideal or only an institution by what individuals actually attain? It depends on what they can attain under the given circumstances; on what the institution through all given means wills and points out that its members should attain."

Perhaps this is just a coincidence, but it is interesting to note that this very thought is found 150 years later in the Ritual of the Degree of Apprentice Mason authorized in 1947 by the Gran Logia de Cuba A.L. y A.M.. There, before his initiation, the candidate is admonished:

"Profane, in this Temple you are among men of honor who will help you as guides, as they are committed to support you through the difficulties in life. By your free will and accord you have come to a society that you do not know, bringing with you only your genuine desire to do good... [But] you do not come, profane, to a perfect society, because in all that is human - perfection does not exist; but you have come to an Institution where are found pure and virtuous men from every country who seek, without the political antagonisms nor the intransigence of religions, universal brotherhood and progress by means of instruction, love and charity, that will make brothers of all rational beings, be it in the joys of happiness, as in the pains of misfortune."

Why the need of an organization apart from the greater society? Fichte's answer:

"Moreover, I do not say that Masons are necessarily better than other men, nor that one cannot reach the same perfection outside of the order. It is quite possible that a man who had never been taken into the society of Freemasons could resemble the picture set forth above, and there actually comes to mind at this moment the picture of a man in whom I find it eminently realized; and he at most knows the order only by name. But the same man, if he had become in the order and through it what he has become by himself in the greater human society, would be more capable of making others the same as he is, and his whole culture would be more social, more communicable, and directly, also, essentially modified in its inner self. What comes into being in society has in practice more life and strength than what is produced in retirement."

(2) What is (and what should be) the relation of Masonry to other human institutions, especially to those directed toward similar ends, and what is its place in a rational scheme of human activities?

Fichte's conception of individual personality and its value led him to oppose any idea of merging or excluding the moral unit in the political or any other organization. Thus each of us may be in any number of groups or associations or relations and continue to be an efficient professional or man of business, a faithful worker, a loyal citizen, a devout churchman, and a Mason at the same time. Masonry is not to supersede calling, government, or church; it is to supplement them. It is to help us be complete, well-rounded men as well as the efficient, patriotic, devout men which we are or should be outside of the Order.

As to the relation of Masonry to the church, we must remember that down to the Reformation and in parts of Europe much later, and down to the French Revolution, the church had vigorously repressed freedom of thought and free science and had by no means made for the development of man's personality to its highest unfolding. The church, says Fichte, cannot make men devout. The man who is devout from fear or from hope of reward only professes devoutness. Devoutness is an internal condition, an enduring frame of mind, not a temporary product of coercion or cupidity of reward or emotional excitement.

Like the state, the church may be an agent of social control in restraining men's instinct of aggressive self-assertion. It can point out to men their relation to the life to come and the duties they ought to be adhering to for the very and sole reason that they are duties. At the same time Fichte warns us that religious militancy and intolerance (which should not be the primary function of churches) compounds the one-sidedness of men - the very condition from which Masonry had the task of delivering them. To be sure, Fichte does not identify Masonry with religion, as Oliver did.

As to morality, it will be remembered that Krause considered that the purpose of Masonry was to put the organization behind morals, as the church was an organization behind religion and government or the state an organization behind law. Fichte holds that morality means the doing of one's well understood duty with absolute inner freedom, without any outside incentive, simply because it is his duty. Consequently, there is no specific Masonic morality, and morality needs no special organization behind it.

(3) What are (or should be) the fundamental principles by which Masonry is governed in attaining the end it seeks?

Fichte:

"All that looks to differences among men, whether to skill in art or learning or virtue, is before Masonry profane. But Masonry itself is profane in comparison with moral freedom since that is the all-holiest compared to which even the holy is common. This conception, firm and thoroughly defined and clear in itself, we must undoubtedly make a canon of Masonry and a principle of critique of everything Masonic if we have to set up such a critique ... Another is, to be sure, to put it shortly, the training of the spirit and the impetus to receptivity for morality, the training of external morals and of external uniformity to law. This of course belongs to Masonry.

Now the picture of Masonry, as it is in and of itself, or uniquely can and should be, will govern your soul. I draw this picture as yet with few strokes. Here men of all walks of life come freely together and bring into a hoard what each, according to his individual character, has been able to acquire in his calling. Each brings and gives what he has: the thinking man definite and clear conceptions, the man of business readiness and ease in the art of living, the religious man his religious sense, the artist his religious enthusiasm. But none imparts it in the same way in which he received it in his calling and would propagate it in his calling. Each one, as it were, leaves behind the individual and special and shows what it has worked out within him as a result. He strives so to give his contribution that he can reach every member of society, and the whole society exerts itself to assist this endeavor and in this way to give his former one-sided training a general usefulness and all-sidedness. In this union each receives in the same measure as he gives. Just through this that he gives it is given him, this is to say, the skill to give."

Both from his knowledge of the institutions of antiquity and from the Old Charges, Fichte had learned that throughout recorded history there had been systems of secret instruction designed to perfect those who were inducted. These secret instructions, systems of mysteries or a brotherhood have supplied the deficiencies of the one-sided training in society.

Such instruction, he holds, can properly be given orally (in contrast with academic training which may use books or manuscripts), may be dogmatic, and imparted by myths, allegories and symbols.

Let me conclude with Fichte's own words, words which, in my view, should be cast in stone at the entrance of every Masonic Temple:

"One who in viewing the deficiency in human relations, the unserviceableness, the perverseness, the corruption among men, drops his hands and passes on and complains of evil times, is no man. Just in this that you are capable of seeing men as deficient, lies upon you a holy calling to make them better. If everything was already what it ought to be, there would be no need of you in the world and you would as well have remained in the womb of nothingness. Rejoice that all is not yet as it ought to be, so that you may find employ and can be useful toward something."

On closing, my brethren, let me remind you that what I have given you this evening is by no means the entire Philosophy of Masonry as seen by Preston, Krause, Oliver, Pike or Fichte - To do that it would take a long, very long time. I just gave you a taste of it.

At your initiation the Junior Warden declared unto you that "Masonry is not only the most ancient, but the most moral human institution that ever existed, as every character, figure and emblem has a moral tendency and serves to inculcate the practice of virtue in all its genuine professors." While walking on the Mosaic Pavement you were exhorted to act by REASON, to cultivate HARMONY, to practice CHARITY, and to live in PEACE with all men. At the closing of his lecture the J. Warden informed you that the Tenets, or fundamental principles of Ancient Freemasonry are Brotherly Love, Relief and Truth.

Brotherly Love

This tenet, or fundamental principle, is an essential element which binds all Masons to each other, as they have pledged themselves to exercise it and it is one of the greatest duties of a Freemason. On this principle, Masonry unites men of every country, religious belief and opinion in a bond of true friendship. Brotherly Love also manifests itself in the second tenet of relief, which is one form of charity.

Relief

Masonic relief takes for granted that any man may be in temporary need of a helping hand. It can take many forms, such as alleviating misfortune, soothing calamity, helping to restore peace to a troubled mind, and so on. This is one of the natural and inevitable acts of Brotherhood.

Truth

Truth is a vital requirement if Brotherhood is to endure. As Masons, we are committed to being honest and truthful with other people. The Masonic Fraternity teaches a man to be faithful to his responsibilities to God, his Country, his fellow man, his family and himself. The Masonic principle of Truth also teaches a man to pursue knowledge and to search for wisdom and understanding. For only in this way can he grow and become a better person.

Also, perhaps you have forgotten, when you graduated from Apprentice to Craftsman (too soon and too easily in our Grand Jurisdiction) you affirmed, not quite sure of what you were saying, that Freemasonry is "a system of morality, veiled in allegory and illustrated by symbols."

As Fellowcrafts, you were prompted to extend your researches into the hidden mysteries of nature and science. In your search and pursuit of knowledge you may stumble upon questions and find no answers. Well, go to your older brethren in your lodge - as M. Masons they were charged to give you assistance. If you find them not much more knowledgeable than yourself, then make use of the research others have provided in online forums, such as this, or this; there you will find much information on the history of Freemasonry, its philosophy and its organization.

If you are motivated, satisfied and proud of being a freemason, offer an opportunity to those who you love and respect to partake in the experience. No matter the race, station or creed, all just and upright men, free by birth, of mature age, sound judgment and strict morals may seek membership in our Institution. The institution (perhaps not so much in our Grand Jurisdiction) offers these men the tools necessary to generate in themselves the inner process of intellectual, moral and spiritual transformation. Aiming for this transformation, the institution generally guides and provides a methodology which enables each member to generate his own inner light and to reach full and complete mastery of his existence. But the depth and height reached by each member depends on his own efforts, perseverance and commitment. The goal is clear: to make of himself a new and better man, tolerant of the diversity of others, and desirous of contributing to the progress of all humanity.

Finally, I must express again my gratitude to The Supreme Council 33° Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, Northern Masonic Jurisdiction for giving me permission to utilize their material, and to the late Bro. Roscoe Pound for creating it. Thank you for your patience.

Presented by Bro. Vincent Lombardo at Doric lodge of A.F. & A.M. No. 316 G.R.C. November 23, 2006

Notes:

1. Roscoe Pound

2. William Preston

3. Karl Chr. Friedrich Krause

4. Rev. George Oliver

5. Albert Pike

6. Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Other Relevant Sources:

Masonic Philosophy

The Builder Magazine 1915 - 1930.

A Concise History of Freemasonry

The Organization of Freemasonry

Masonic Authors "The Bad, the good and the ugly" by Bro. Alain Bernheim 33